Not all body fat is created equal. While some fat serves essential functions, visceral fat is different — it’s metabolically active and closely linked to many of the chronic conditions we aim to prevent through proactive care.

At Clay, visceral fat is a key data point we monitor because it often tells a more accurate story about health risk than the scale alone. Even individuals who appear lean or fall within a “normal” BMI can carry excess visceral fat. This guide is designed to help Clay members understand what visceral fat is, how it impacts long-term health, and which lifestyle strategies are proven to reduce it in a sustainable way.

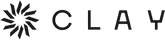

What Is Visceral Fat?

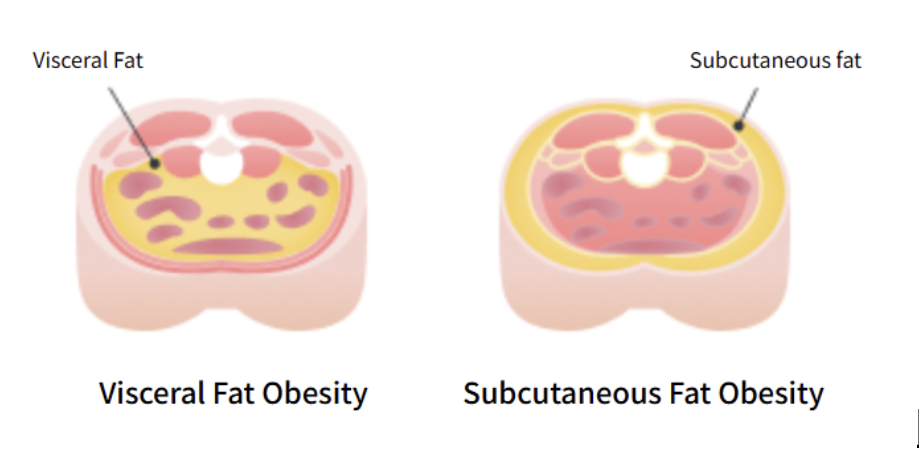

Visceral fat (visceral adipose tissue, VAT) is the fat stored deep inside the abdominal cavity surrounding key organs (liver, pancreas, intestines, and kidneys). It is metabolically active, releasing hormones and inflammatory molecules that affect whole-body physiology. This is fundamentally different from subcutaneous fat, which sits under the skin and is relatively less harmful.

In a snapshot:

- Location: Surrounds internal organs in the abdomen

- Activity: Secretes adipokines, cytokines, and free fatty acids that interact with metabolic and immune pathways

- Health impact: Strongly linked to cardiometabolic disease, cognitive decline, and systemic inflammation

The Harmful Effects of Excess Visceral Fat

1. Metabolic Dysfunction

Visceral fat is tightly linked to insulin resistance, dysregulated glucose metabolism, and elevated circulating fats (hallmarks of metabolic syndrome). It contributes to pro-inflammatory states that drive metabolic disease progression.

Studies show that visceral fat predicts metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic risk independent of BMI, meaning even “normal weight” individuals can be at risk if VAT is high.

2. Cardiovascular Risk

Visceral adiposity is associated with:

- Atherosclerosis and arterial stiffness

- Hypertension

- Elevated triglycerides and dyslipidemia

- Increased risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality

3. Cognitive Impacts and Brain Aging

Emerging studies associate higher visceral fat with reduced cognitive performance, including executive function and processing speed. These associations persist even after adjusting for other risk factors, suggesting a direct link between VAT and brain health.

Mechanistically, visceral-associated systemic inflammation and insulin resistance may impair cerebral blood flow and increase amyloid deposition (a feature of Alzheimer’s disease).

Primary Causes of Visceral Fat Accumulation

Visceral fat accumulation does not arise from a single factor, it results from an interplay of lifestyle and physiological drivers:

Dietary factors:

- High intake of added sugars, refined carbohydrates, and saturated fats

- Frequent alcohol consumption

- Ultra-processed foods correlate with increased VAT deposition

Lifestyle and physiological factors:

- Sedentary behavior and lack of physical activity

- Chronic stress and elevated cortisol

- Poor sleep patterns

- Hormonal influences

Visceral fat increases cardiovascular risk by driving inflammation, insulin resistance, and arterial dysfunction.

Best Evidence-Based Strategies to Reduce Visceral Fat

1. Nutrition: Protein + Fiber Focus

A diet higher in lean protein and fiber supports satiety, improves glucose regulation, and enhances metabolic efficiency (key factors in reducing visceral fat). High-quality diets rich in vegetables, legumes, and lean protein sources are inversely associated with VAT.

- Aim for moderate protein with every meal

- Prioritize whole foods over processed foods

- Include high-fiber options (e.g., beans, fruits, vegetables)

2. Exercise: Cardio + Resistance Training

Regular physical activity is one of the most effective ways to reduce visceral fat:

- Aerobic exercise (moderate to vigorous) improves fat oxidation

- Resistance training helps preserve lean mass while enhancing metabolic rate

- Combined approaches have stronger effects on VAT reduction than either alone

Guidelines:

- 150–300 minutes of moderate or 75–150 minutes of vigorous activity per week

- Incorporate strength training 2–3 days/week

3. Sleep: 7–8+ Hours Is Protective

Shorter sleep durations are significantly associated with increased visceral fat independent of other factors. Ideally, 7–8 hours of quality sleep per night supports hormonal balance and metabolic regulation.

4. Manage Stress & Cortisol

Chronic stress promotes visceral fat accumulation via prolonged HPA axis activation. In simple terms, this means the body stays in “stress mode” and continues releasing higher levels of cortisol, the primary stress hormone. Cortisol raises blood sugar to provide quick energy, but when it remains elevated for long periods, extra fuel is more likely to be stored as fat, especially around the abdominal organs. Reducing stress through structured methods (e.g., mindfulness, therapy, active recovery) can attenuate this signal and support VAT reduction.

5. Hydration & Overall Recovery

Proper hydration, alongside sleep and recovery practices, supports metabolic efficiency and reduces systemic inflammation, both important for adipose tissue health. Staying well-hydrated doesn’t directly “burn” visceral fat, but it supports blood sugar control, stress regulation, and appetite management, all of which influence where and how the body stores fat.

Fat Types — Subcutaneous vs. Visceral

Checklist: Lifestyle Targets for Low Visceral Fat

- Balanced diet: protein + fiber

- Regular exercise: cardio + strength training

- Quality sleep (≥7 hrs/night)

- Stress management

- Limit alcohol and added sugars

- Stay hydrated

Bottom Line

Visceral fat is not just “belly fat” but an active endocrine organ associated with metabolic, cardiovascular, and cognitive risks. It can develop even when weight and BMI look normal, which is why assessing body composition, not just scale weight, matters.

The good news? Lifestyle modifications, like our Foundational Five (Protein, Sleep, Hydration, Steps, Fasting) are proven and evidence-based ways to reduce visceral fat and improve health outcomes. Consistency over time trumps short-lived interventions.